Human Bust Introduction

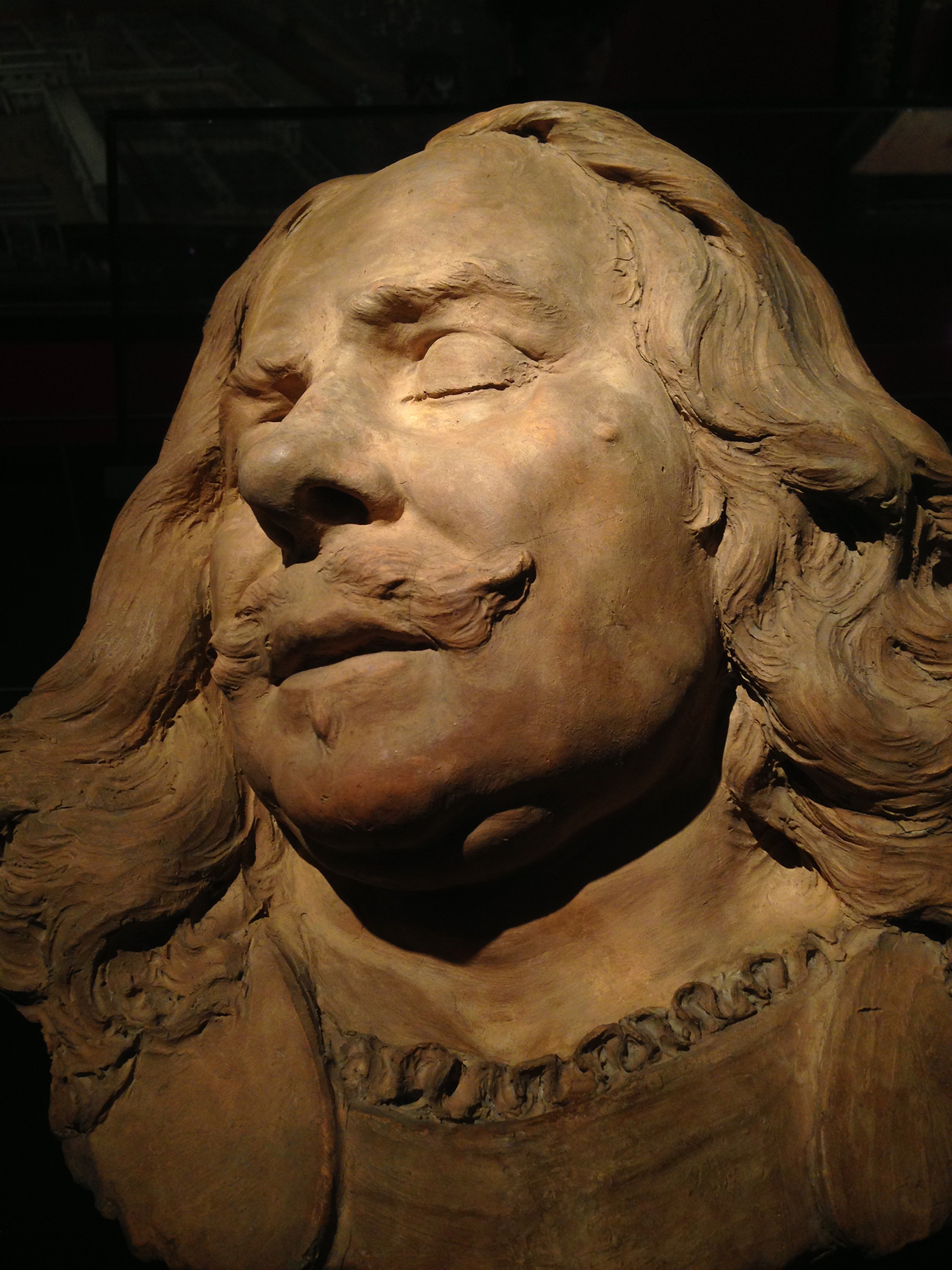

The Human Bust project is complex and involved. Although it only requires simple tools and materials, the real challenge is in understanding detailed physical anatomy, proportion, volume, exprerssion, character, personality, composition, material qualities, and the nature of shadow and light. Typically, sculpted busts use monochromatic materials, which means that depicting color, value, and contrast is done only by manipulating the height and depth of your materials in space, in relationship to other forms.

Facial expression is subtle and complex in a beautiful way. Human beings are incredibly well adapted to pick up on facial cues. A good part of our brain is dedicated to facial recognition, almost entirely subconcious. We react instantaneously to the smallest changes in expression. Because much of our recognition abilities is done without awareness, discerning the true physicality of the face, head and body is difficult. You must work to bring into your conciousness the shapes and volumes that make up a personality.

Since we are so good at responding to subtle cues it is hard to understand how small these cues really are. Tiny changes make a big impact. When someone other than yourself studies what you are making, it will typically be easier for them to see things that are in error than it is for you. Why? Because they can look more objectively at your work; they see it from a fresh perspective just as though they were looking a real person in real time. They will use their own automatic responses to pick up on things that seem out of place. When we are fully involved in our own creations, we often become overwhelmed with the problem at hand, focusing on one thing in great detail while overlooking others. This is why regular feedback is important on the human bust project.

You will create either a self-portrait, or work from a subject you can physically reference like a family member, friend, classmate, or someone else of artistic interest. For any living persons who are not public figures - or your own children - you need to get their permission to work from them.

What is a Bust?

Sculptural portraits that include a portion of clothing, torso, shoulders and/or collarbones are considered "busts". The term bust comes from the Latin word bustum, which refers to a tomb. In ancient times, tombs often contained sculptures of the upper chest and head of those entombed. A bust sculpture is truncated above the belly at the lowest, and above the breast line at the highest. Most busts do not include full arms, and if included at all are usually truncated between the shoulder and elbow. This makes the sculpture focus on framing the head rather than the body.

We Are Not Creating a Head Study

Reference Sources/Materials

The best resource is working live, including looking at yourself in a mirror in the classroom. If you can work from your subject while they sit for you, this will make understanding their forms easier than only from looking at photos. Photos, by nature, are flat and can only hint at 3-dimensional volumes. When a subject is not able to sit for you, a high quality series of photographs must be taken, which includes full in-the-round viewpoints and lots of detail shots from many angles. You should only use 2x or 3x zoom, not 1x or fisheye with your camera.

Lighting is very important in order to understand the volumes in your subject. Light your model so that you can see sculptural contours of their face, neck, and other body parts necessary for your work. Flat, even lighting, such as from overhead banks in classrooms and commercial spaces, is not desirable. This kind of lighting is designed to reduce shadows, making for poor depictions of volume. Harsh, direct light from point sources such as the sun also make understanding the form more difficut. In this case shadows and high contrast can make it difficult to discern complex and subtle contours.

Good lighting is when several softer, directed light sources at chosen angles are used to capture spatial dimension in the subject.

Scale

The scale of a bust in this class must be either life-size or a little bit larger than life. It is easier to understand what you are making and to do physical comparisons to a real-life subject at actual scale. It is not to be made smaller than life. Many problems arise when working small, including having to work with miniature tools, difficulty transferring measurements from the live model to the miniature, and the inability of the material to take very fine detail. Special materials and tools must be used to work very small.

When working larger than life certain factors must be considered: the work will be heavier, take more time, and will make direct measurements from real life more challenging. However, it is common practice to make a bust larger than life if it is to be in a public setting. Monumental scale is a whole other world, and is necessary only if the bust will be placed in a large space, or outdoors. Life sized sculptures in large spaces feel very diminished. A monument needs to be large to have impact - or even to feel like it is a natural size when competing with architecture and landscape.

Clothed or Not

A bust can either depict clothing or be unclothed. Both are appropriate based upon the aesthetic choices of the artist. Clothing has compositional impact on the sculpture, and conveys a time, place, and style of the subject. If clothing is depicted, make aesthetics a factor in choosing what should be worn. If the bust is unclothed, make sure to acquire visual references of the necessary torso and shoulder details - obviously this choice is a personal comfort one, and always the model has full decision power. How does the style of clothing depicted in a bust impact your view of the piece?

Hair

A full depiction of hair, if present in the subject, is a requirement in your sculpture and has a large impact on its expressiveness and compostion. If the subject has long hair, and this is a defining feature of their persona, it will dictate the overall size of a bust. Truncating hair looks odd, and must be avoided. Sometimes it is sculpturally appropriate to put long hair into a bunch, or to direct it in a fashion that flows around the shoulders for movement and visual interest.

Pose

Overall, besides how hair may frame a bust, the pose and amount of torso to include is an aesthetic and practical decision. The practicality aspect is influenced by how much space there is to display the bust, and how much time you have to complete it. The aesthetic decision includes composition and story telling. How do the bust elements work together in the art piece, is there an implied motion to the body pose, and what does the inclusion or exclusion of details tell you about the individual?

Materials

Typically the bust is sculpted in water-based clay, as this is the least expensive option that can be continually worked through additive and subtractive methods. Clays have plastic qualities that make it easily formable with simple hand tools. The specific type of clay traditonally used in class has been recycled from an amalgamation of leftover clays re-pugged in the ceramics department at SRJC. Other clays have finer properties for use in detailed sculpting, but cost more.

After the clay work is complete, a variety of methods can be used to make the piece permanent, from firing of the clay - if prepared and worked properly from the start - to making complex molds and casting in plaster, cement, resins, and the like.