Vemco's Design Evolution

Over the decades that Vemco was in business they evolved the basic form of their compasses to improve on materiality, weight, aesthetics, and drawing capacity. One of the basic tenets of Vemco was their desire to make compasses that were capable of drawing a wide range of diameters so that customers would not need a large number of different compasses to make the full range of circles.

Another tenet was to make very strong compasses that used steels requiring modern manufacturing processes to fabricate them. This strength issue was related to their understanding that drafting was changing from a predominantly pen-drawn process to pencil. In order to allow for graphite drawings of sufficient contrast that could be reproduced in blueprint form, they needed physically strong compasses, allowing for greater drawing pressure. The use of cold-rolled steel and stainless steel made the compasses more robust and capable of being made of thin stamped sheet, rather than heavier and soft metals such as brass and German silver used in traditional compasses. Other compasses were typically either cast and machined, or machined from solid stock.

This page discusses the changes over time of the 6-1/2" compasses created by Vemco.

The standard by which Vemco was known was the C-110 compass. This was their best-selling compass for nearly 20 years. The SC-110 was the higher quality stainless steel version, and the C-40 was their student-grade version. The price for each in 1956 was: C-40, $3.25; C-110, $4.95; and SC-110, $5.95. By 1959, Vemco reduced the price of their top-of-the-line stainless steel SC-110 to $4.95. At the same time, they phased out Red Dot compasses in their instrument sets, and changed them out to stainless steel at no extra cost. Oddly enough, people could still order Red Dot sets if they specified it, but it would cost the same as Blue Dot.

The Red Dot C-110 weighed around 50 grams, whereas the Blue Dot SC-110 weighed 42 grams, and the Yellow Dot C-40 weighed 52.4 grams. Why the difference in weights, when all were stamped from the same machinery? It amounts to differences in materials and the amount of finishing done to them. Chrome is number 24 on the periodic table, and was used to plate the C-110; Nickel is number 28, and was used to plate the C40. The C40 also was unrefined from the initial stamping, so it had more metal in it. For both the C-110 and the SC-110, the edges were hand-finished, removing small amounts of metal. Because the SC-110 was made from stainless steel it required no plating.

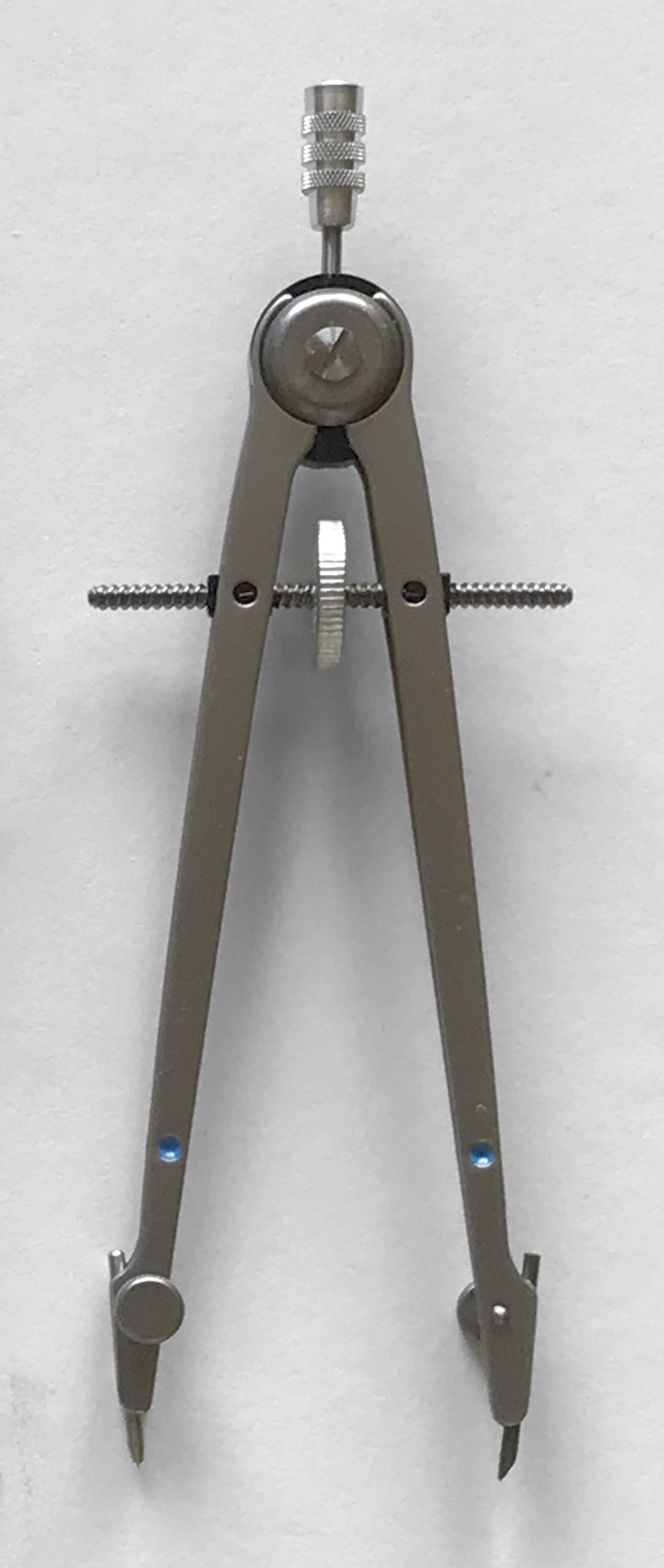

At some point, Vemco designed their first Speed Bow compass. "Speed Bow" refers to a compass that can be adjusted very quickly. Instead of the usual slow turning of the wheel to make large adjustments, the Speed Bow compass had a button that when depressed, released the screw threads and immediately sprung the compass open. How to approximate the desired opening: while depressing the button, squeeze the legs to the desired opening, and release the button. Fine adjustments could be made with the thumbscrew.

This awkward design had many flaws. For one, the bow spring was very powerful, so pushing the button without holding the legs in place caused rapid and violent opening of the compass, often pinching a finger along the threads and ball-end. Also, the compass was no longer bilaterally symmetrical, making holding it off-feeling. Further, having the threads release as they did had the potential to cause damage to both the internal and external threads as the parts rapidly rubbed against one-another. A fourth problem was that the thumbscrew was on the outside of the compass. They had to incorporate a ball at the end of the threads to both protect the user from the long extension, and also prevent the compass from flying apart if it sprung open too fast. Finally, because there was only one thread engagement location (where the traditional compasses have two), adjusting with the thumbscrew took twice as long.

Notice that this Speed Bow compass utilized the same stamped parts found in their original 6-1/2" compasses - in the case shown here, Yellow Dot legs. As a result, the legs contained cut-outs for accommodating the thumbscrew, which were no longer needed. These vestigial openings were useless, where form no longer followed function.

A transformative design change was made when Vemco created the Slimline compass. They created two versions, possibly three. Shown above is Yellow Dot (moden number unknown). They may have had a Red Dot version too. The SC-500 was their Blue Dot stainless steel Slimline Compass. This iteration incorporated several mechanical and visual revisions. The most striking was the leg shape. No longer was the thumbscrew cutout necessary, as the legs gently curved inwards to allow the ends to meet while simultaneously making room for the shumbscrew. Further, the pins that locate the nuts in the legs are very small, allowing the outside of the legs to also be reduced significantly into a clean sweep.

Another big change was in the position of the thumbscrew, where it was raised closeer to the handle at the top. This allowed the threads to be much shorter than previously, even with the same thread pitch, allowing the compass to open significanty wider than in the original design. This compass could open from 1/16 to 13-1/4"! In other words, not only could it draw smaller circles, it could also draw 3-1/4" bigger circles than its predecessors- yet its legs were the same length.

Although the Slimline and the original compasses all had the same thread pitch of 40 tpi, they were not the same diameter. The orignals had a 5-40 thread, and the Slimline had a 4-40 thread. Since they both had the same number of threads per inch, a full rotation of the wheel moved the legs apart at that location by 1/20th of an inch (1/40th x two nuts). The combination of a smaller thumbscrew diameter and closer positioning to the spool, meant that the compass opened faster than its predecessors.

Visually, the handle knurling changed from the previous models. The earlier vesions had one wide band of knurling, whereas the new knurling was in three narrow bands.

The bow spring, handle, spool, thumbwheel, and clamp screws all were smaller, and the thickness of the stamped metal legs were reduced from the original 14 ga. to 17 ga. The legs were also much narrower. Even though the legs were the same as in previous models, the overall height was shorter due to a reduced bow spring and handle dimension. All of these changes meant that the Yellow Dot Slimline compass shown above weighed only 31.4 grams. That is 21 grams lighter than the Yellow Dot C40! Not only was it incredibly light, it also had a bigger capacity!

The Blue Dot L-560 borrowed its desin ethos from the Slimline series, but with a return to the thicker 14 ga. metal, larger bow spring, spool, thumbwheel, and clamp screws. The legs also bulked up. Unknown is if Vemco released these designs in anything besides stainless steel Blue Dot.

The L-560 compass maintained the same capacity as the Slimline compass, meaning it also could also open from 1/16 to 13-1/4". Its thread size changed back to 5-40, and its overall thread length also returned to the 2-1/16" of the originals. The reason that the circle capacity was greater than in the originals was that the nut positions were slightly closer to the spool.

The earlier versions of these instruments had a brushed finish, whereas the later (and final version) had a matte bead-blasted finish. The later bead-blasted version had one handy new feature: the model number was stamped on the side of the thumbwheel. This version, the S-570 (small bow compass), and the SB-550 (Speed Bow compass) all had their model numbers demarcated this way. Vemco carried the new three-band knurling into all of their final compasses and dividers. The L-560 is a highly refined stainless steel compass weighing in at between 47 and 50 grams. This is heavier than the SC-110, but nearly identical to the C-110. This compass was available until Vemco closed its doors in 2014.

Vemco's final Speed Bow design, the stainless steel Blue Dot SB-550 shared many aesthetic fearures of the L-570, with the notable exception of a lack of a bow spring. Instead, they incorporated the erector and cup washer design originally created for their dividers. It no longer needed a bow spring, because the threads were radically changed. No longer were they 40 tpi; they were 20 tpi. The outer thread diameter was 1/8".

The overall length of the compass was slightly shorter than the L-560, while incorporating the same handle size. Because the bow spring was replaced with the friction cups, the legs grew in length. With longer legs, even though the nuts and thumbwheel were the same distance from the pivot positon, for every increment the nut position opened, the points moved faster. This, in combination with the very coarse thread count, meant that the compass opened and closed more than twice as fast as the L-560.

Given that the SB-550 was one of their last products, Vemco used a dense black plastic for their erector and the nuts that engaged the screws. Cleverly, they were able to utilize the compressive nature of their spot-welded legs to capture the plastic nuts and provide friction against the threads, making the desired setting of the compass very firm. The plastic thread piece was injection-molded in two halves, hinged over the threads so no machining operations were needed for the nuts.

The SB-550 weighed 50 grams, or the same as the L-560 and the C-110. Due to its geometry, it was capable of drawing the largest circles yet: 13-3/4". It takes 6 thumb motions to open the SB-550 two inches wide, and 17 thumb motions to open the L-560 the same amount. All of this speed, along with the extra friction required to hold the compass in rigid set position also had a drawback. The force needed to turn the wheel was much greater, fatiguing the hand. Some other companies who have innovated their own speed bow designs also removed the bow spring. Further, some have dual push buttons or levers to release the threads, allowing rapid opening. Some have a special rounded thread geometry allowing the compass legs to simply be pulled apart, spinning the thumbwheel in the process. To name a few, Alvin and Rotring both came up with rapid-adjustment mechanisms.