Essay: Value in Process

By Michael McGinnis

Introduction

There is theory behind the TGF exercise, and many reasons to approach it from unique points of view. I developed the project after observing how another instructor employed paper forms in their class many years ago. In that situation, students were given printed patterns that they cut out and assembled; the exercise there was not the actual form, it was about mark-making to camouflage the form. I understood the point of the project was to develop an understanding of how the appearance of an object can be visually altered by pattern rather than by 3-dimensional changes to its form. The lesson was not the actual shape of the object at all, which was, in a way, incidental.

My desire was to create an exercise where the physical form itself needed to change over time. This was so that students would gain a deep understanding of the three-dimensionality of an object. The way I could see this succeeding was by first teaching students how to draw up and assemble their own basic forms from scratch. After gaining an understanding of it in pattern form, and then through the process of assembly, they would have enough experience to make their own changes to the form. This idea lead to the concept of 6 sequential forms; requiring more in the series seemed unnecessary, and less seemed too small to end up with truly unique forms.

My Own Growth Through the TGF Project

Students may assume that instructors know what they are doing, and that they carry a natural authority through position, experience, and time. This expectation is reasonable, and for the most part true. However, when an instructor first starts teaching, or when they create a new project entirely on their own, they do so from a theoretical rather than practical position. This was the case with my creation of TGF. I witnessed a project that I thought was interesting, but considered it a jumping off point for both my students' and my own growth. I didn't know if the project would succeed or fail. This should sound familiar to students, as I try to make it clear that they too should not let fear of failure stop them from trying.

It may seem interesting, or maybe even irritating to you, but at the beginning of all this I had no idea how even the most basic patterns were created. When it came to precise geometric volumes, I had personally never made more than the simplest cubes. Of course, I had a decade of experience as a sculptor making 3D objects of art, but they were not at all like these. So I did not know how to even draw a tetrahedron, and certainly didn't know how to lay out a pentagon. What I did know was how ideas evolve over time, as my own artwork, furniture designs, and inventions did just that.

I had to learn how basic forms were drawn, and how to communicate this to students. I also had to learn how important it was to use quality tools, as this affected accuracy and ease of design. Most of all, I learned from students about what was possible. The range of simple transitions presented to you in TGF are the result of what students just like you discovered and tested. I gained experience through them, and now pass that information on to you. At this point, I think I have a very deep grasp of the project, both conceptually and practically.

When I first started the project I did not know where it would lead, and I was too restrictive. For example, without hindsight I thought it was important that every subsequent form matched its predecessor in scale: if a triangle was 2" across in the first piece, it needed to be the same in the second, etc. If someone did change the scale from one object to the other, the rest must likewise scale in sequence. However, I learned over time that scale sometimes had to change for practical reasons that had nothing to do with aesthetic purity in the series. So I let that go. I am pointing this out to demonstrate that I, too, expect to let experience teach me things.

The lessons in TGF are not at all about the specific objects being made; it is about evolutionary thinking in design. The paper forms are merely the vehicle for exploring the intense and valuable creative process that we all need to foster in ourselves. The exercise of stretching physical skills and the mind are basic and essential to the human condition.

Failure is Not an Option, it is an Expectation

Everyone fails at some point. It is not the failure that is important, it is how you respond to it that matters. The best minds have all made plenty of mistakes, misjudgements, and miscalculations. From failure comes a deeper understanding of the underlying concept. It is essential to make mistakes. It is the best way to truly know a subject, and it is a testing ground for the boundaries of an idea or process. It is nature's way of evolution and survival.

It is natural to feel uncomfortable with failure, as it is often frowned upon in family dynamics, in social and professional experiences, and in one's own ego. But letting go of fear related to failure is significant and very powerful. It is how truly innovative ideas come to life, and also how people can better reach their potential.

When something does not work out, there are reasons. Studying these reasons teaches the limits of an idea, and also how to avoid those problems. Falling off a 1' high curb and skinning your knee, helps you avoid falling off a 100' cliff. But if skinning your knee made you avoid climbing stairs or crossing the street, you have let failure take over your life. Our biology is built to heal us of our scrapes and bruises because it is an expected part of life.

Permission to Wander

A crtitcal aspect of TGF is letting go of a specific end goal, other than to make six interesting forms in series. Your brain has an amazing ability to think ahead; it is supposed to do that! It lets you anticipate an outcome so that you can maximize your chance of survival. Rest assured, you are still going to survive in this class if you break from planning too far ahead. In fact, your mind will stretch further if you do break from this mindset. Think of it this way: you are on a drive to visit home. You have taken that road a thousand times before. At the third turn, you always turn right. But one time you decide to turn left. You drive and turn many times, eventually discovering that you are at a dead end. You now have a completely new understanding of the geography, and saw some beautiful houses and landscapes along the way. Even if you didn't find a new route home, you found out how NOT to get home. And maybe you found the home of your dreams.

I try to explain how, in the TGF project, planning too far ahead is a limitaion. If you fall in love with a form you have seen and make a beeline to recreating that form, you are stopping yourself from creating someting even more beautiful and unusual. Think of it this way, if you can picture the outcome, you are already capable of aspects of its creation. Learn to do something you were just a moment ago incapable of. The goal of the project is to let go of the "knowing", and take an unexpected turn at each evolution.

Innovation Through Evolution

Nature does not evolve by seeing ten steps ahead. It tries an idea, and either succeeds or fails. Either way, it is an evolution. Living forms respond to environmental change. This dynamic response to change is what makes life so diverse on Earth. Dinosaurs were incredilby amazing and successful creatures for hundreds of millions of years, but they could not adapt well to rapid environmental changes. Other life forms could, and as a result, we exist.

Baby Steps

It is not typical, practical, or expected that you are a paper form savant. Maybe you are, and good for you! But most are not. However, EVERYONE can do an amazing job on invention and innovation if you allow yourself to make small changes to an idea. You see something that needs to change in some understandable way, and you make that change. Then you look at the result, and consider what can change about that to make it better, more interesting, more practical, or easier to make, and you do it.

Here is an example of how I have personally applied this concept in my own creations:

Over my years of teaching I have seen how the basic Platonic solids can be used to easily create fully enclosed volumes. A fantastic basic volume for the Lamp Project is the dodecahedron. It is a 12-sided enclosure made entirely from pentagons. Making pentagons has always been reasonably difficult. For years, I would spend a fair amount of time teaching individuals how pentagons were drawn traditionally. Here are four methods I would teach:

- Drawing a Pentagon with a Compass Set Only Once

- Drawing a Pentagon with a Given Side Length (no Protractor)

- Drawing a Pentagon with a Given Side length, using a Protractor

- Drawing a Pentagon Within a Circle

I found that many students avoided pentagons because they were hard to draw, even with training. Because of my deep dive into pentagons related to teaching, I discovered the fascinating relationship of the proportions within the pentagon. If you take the length of the pentagon's base - the same length as all of its sides - there is a precise relationship to the distance of its apex, relative to the base's end points. The shape is a triangle; but no ordinary triangle. It is isosceles, with the proportion of its base to its sides being the Phi, or the Golden Ratio. This is ancient knowlege - nothing I discovered.

I thought, how could I make an adjustable compass in the shape of an "X" where one end was of length a, and the other was of length b, its golden ratio complement. This is how a proportional divider works, except I wanted graphite points, an adjusting thumbwheel on it, and to have it fixed to the golden ratio. I worried, "someone will poke their eye out".

Then I evolved my idea to a compass that had three legs along the same pivot point that opened to the golden ratio. This idea would require graphite points on the outer legs, and a steel point on the center leg. Compared to the simplicity of my first idea, this new version required me to tackle the difficulty of creating a mechanism that opened two legs at different rates, much like the beautiful golden ratio calipers made for artists.

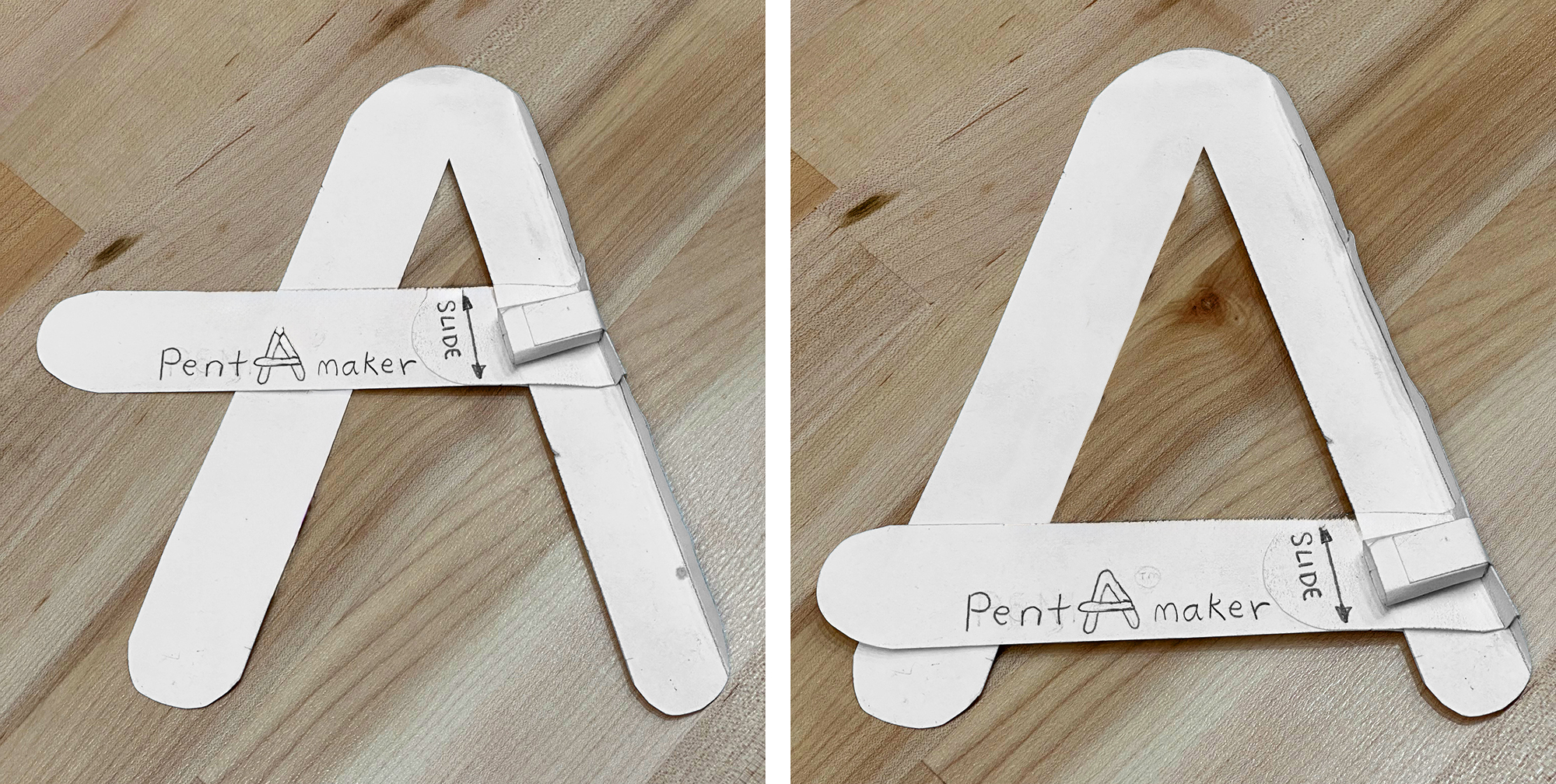

Pent-A-Maker, V1

Then I realized I could create a template that was made from an A-shaped triangle of the correct angle (72 degrees) where the horizontal line of the A was slidable up and down. I made a paper prototype, the first prototype in my quest. It was easy and automatic to set any base length, and then locate the apex position perfectly. But with that device, it was still necessary to employ a compass to find the rest of the pentagon's sides. I called it the "Pent-A-Maker", with the "A" logo drawn to look like the tool. Here is how it lays out a Pentagon (with the assistance of a compass). For this last image, I added rulings.

Pent-A-Maker, V2

That is when I realized I could eliminate the sliding part of the device by removing one of the diagonals on the A, essentially turning it into a slanted L. Rather than have a slidable part, there would be a standard ruler on the horizontal leg and an enlarged golden ratio ruler on its diagonal leg. That way, one could demarcate the zero point of the pentagon, draw its base to a given length along its horizontal ruler, then mark the apex along its golden ratio ruler. If you wanted a pentagon with a 2" base, all you had to do was draw a 2" line, then mark along the golden ratio ruler at the 2. Of course, you still needed a compass to find the rest of the pentagon. I made a wooden and then white plastic working model of the device, now referring to this new design as the true "Pent-A-Maker". It worked perfectly.

Pent-A-Maker Pro

My next iteration came to me when I realized I could add another two legs to my concept utilizing extra standard and golden ratio rulers, making it possible to completely eliminate the compass from the process of making pentagons of any size. This version I called the "Pent-A-Maker Pro". It is effortless to make accurate pentagons of any base length.

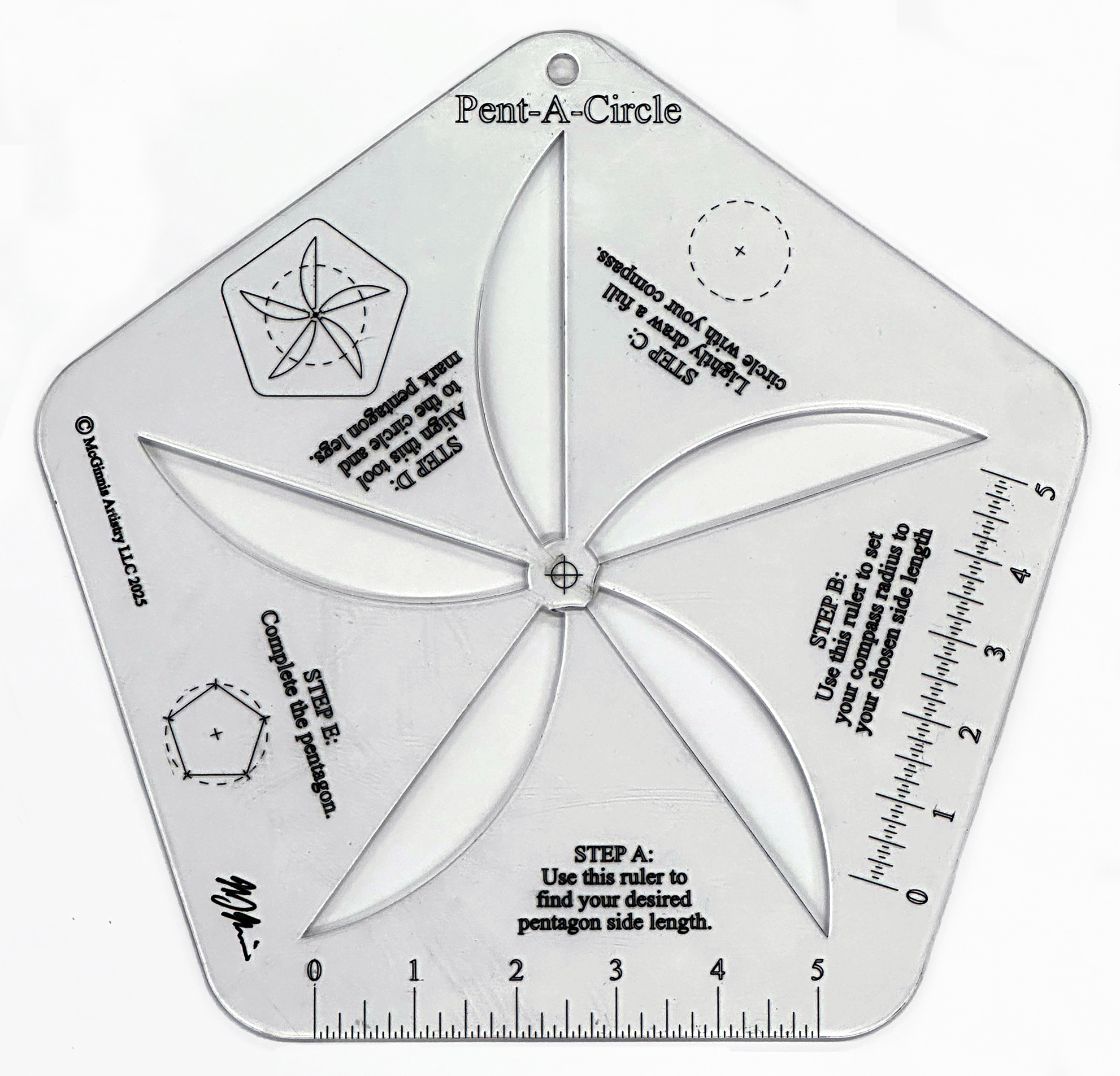

Pent-A-Circle

After working on the creations described earlier, I decided to make one more called the "Pent-A-Circle". This version was to let a person draw a pentagon inscribed into a circle. Earlier in this essay I mentioned a compass method on how to draw a pentagon within a given circle, thus why I made this design. It was made from clear acrylic so users could see the circle underneath. Naming my tools follows the same evolutionary process as designing them.

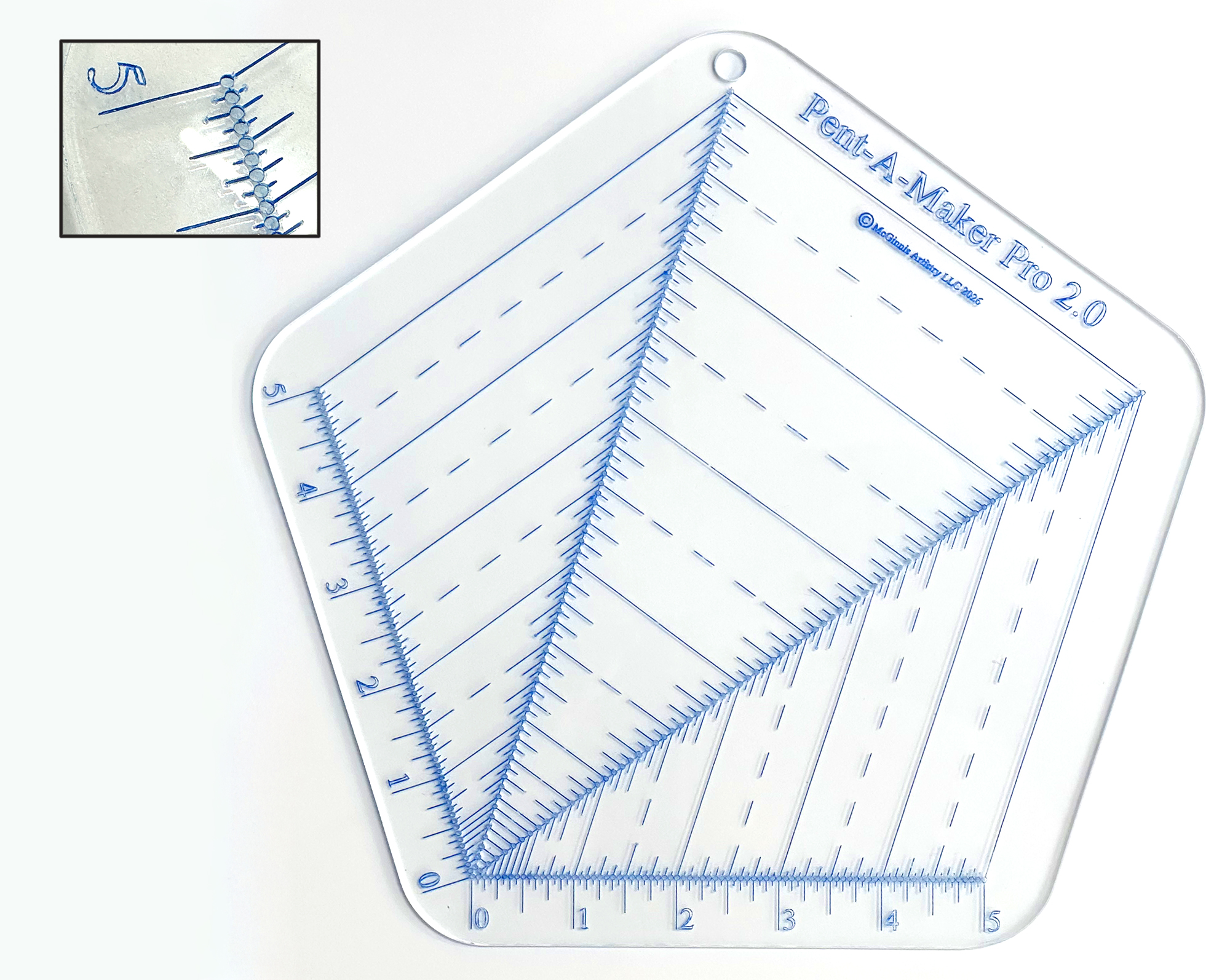

Pent-A-Maker Pro 2.0

In response to a student saying that she was having difficulty marking an accurate pentagon using the Pent-A-Maker Pro due to parallax, I created the model seen above. Parallax occurs when the distance between a measuring tool and the object to be measured is great enough that looking from any angle other than straight on can make measuring inaccurate. All of the previous wood and acrylic Pent-A-Makers were made with 1/8" thick material. The Pent-A-Maker Pro 2.0 has tiny holes at every 1/16" increment along the various lines, making it possible to use a small mechanical pencil or sharp pin to mark the appropriate pentagon vertices. I laser cut the holes to fit the ferrule of a 0.3 to 0.7mm mechanical pencil. Holes any larger would not have been possible to fit at each 1/16". A benefit of not making large through-cuts in the material is that this design allowed the device to accommodate 5" maximum pentagons (where the previous stopped at 4-1/2") while still being the same overall size as its predecessor.

Earlier in my iterations I resisted making a perforated design because I felt that it was not visually pleasing, would not clearly demonstrate the wonder of Phi, and that even though it could be made precisely it might not be used accurately. Precision is when a thing is made to a very tight tolerance. Accuracy is when something is fitted or used properly. With the Pent-A-Maker Pro 2.0, it is possible to mark a very precise vertex in the wrong hole, making an inaccurate pentagon.

In the future I plan to make a revised original Pent-A-Maker Pro with the rules on a beveled edge, so that they terminate very close to the paper, virtually eliminating parallax. Another version may be made from a very thin, strong, elegant-looking material that can be marked well with the laser cutter. If the material is thin enough, parallax would also be greatly reduced.

Simple Conclusion

Everything I describe in this essay is a concrete example of why there is value in process. Even the process of writing this essay helped me clarify and solidify my own ideas on the subject.

Every iteration of my Pent-A-Makers was driven and informed by what came before. I would not have been able to make the Pent-A-Maker Pro without my series of revelations, which would not have existed without the TGF and Lamp Projects, the practical needs of my students, and my desire to do good by you.